I’m counting down my 100 favourite songs of all time. To keep this from becoming a Bob Dylan / Tom Waits love-in, only one track per artist is allowed.

Go to 68: Take Me Out by Franz Ferdinand

Go to 70: Rock Steady by Aretha Franklin

Music is great at being political. But only a specific type – namely, music with words. It’s very difficult and rare for music without words to make clear and precise political points. Which suggests that music is not actually that great at being political.

Very few of the symphonies and sonatas, concertos and chamber pieces from hundreds of years of classical music were written as deliberate political statements. This may have a lot to do with the contexts in which they were created, from classical music’s religious origins to the patronage system that funded the work of many key composers and which no doubt discouraged any overt questioning of the existing political order.

Of course, political meaning is often ascribed to classical pieces, by the composer’s title or dedication, because of its use in specific contexts or due to new critical interpretations.

Beethoven dedicated his Third Symphony to Napoleon as a-then beacon of hope for democratic ideals but the piece itself is often interpreted as being more about the composer dealing with the onset of deafness. And he later withdrew the dedication when Napoleon made himself emperor and captured Vienna, where Beethoven lived.

Though Shostakovich occasionally earned the ire of the Communists ruling Soviet Russia, it was typically for his music containing too many Western influences than any overt criticism of the state. Some suggest that looking west was itself a political point, but it’s also likely that the composer was simply interested in other styles of music.

The screaming violins of Penderecki’s Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima seem to be making a statement about the horrors of atomic war. However, the title was only applied after the composer heard it performed for the first time and sought out an appropriate reference point for the emotion he felt.

While the very existence of jazz music is an act of resistance, individual compositions often require words to fully express the hardships and injustices faced by black Americans, such as when Billie Holiday used the poetry of Abel Meeropol to tell of strange fruit hanging from southern trees. Instrumental pieces like John Coltrane’s Alabama and Haitian Fight Song by Charlie Mingus were inspired by political events but any messages in the music aren’t readily available to the average listener.

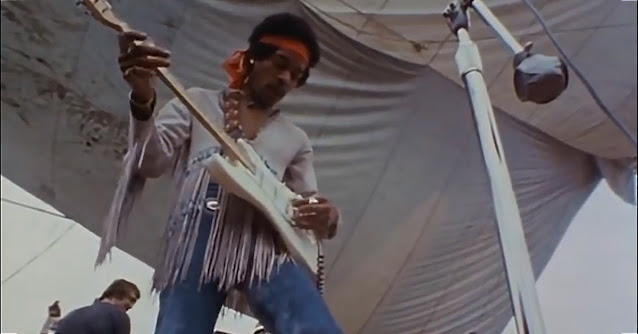

Rock, pop and soul are primarily lyrical mediums and it’s hard to imagine a song without words being able to match the quiet fury of Masters of War, offer the hope of A Change Is Gonna Come or highlight social deprivation like Ghost Town or The Message. Jimi Hendrix distorting his guitar until it sounded like the choppers then terrorizing the people of Vietnam as he wailed his way through a wordless Star Spangled Banner at Woodstock is a notable exception.

Electronic music was political from the off in terms of how its dancefloors helped unite different races, sexualities and classes in a single sweaty circle of ecstasy. But the music’s "one love" messages are typically delivered by vocalists or spoken word samples and it’s telling that when the mighty Orbital listed their 10 favourite politically charged tracks, only one of them was from the world of dance.

That track is Autechre’s Flutter, a clever and adeptly-executed response to the UK’s 1994 Criminal Justice and Public Order Act that banned the playing of music with repetitive beats in public places. On Flutter, no two bars are the same so it could not fall foul of the new law. It’s a bold and provocative statement though the music itself isn’t as memorable as the premise.

Flutter highlights the trickiness of creating overtly political instrumental music. Making a point often requires playing with form, doing something unusual with time signatures, tempos or tonality that has a specific meaning. The listener not only has to be well versed in the set theory so they can appreciate the deviation, but also need the background context. If you don’t know about the repetitive beats ban, Flutter may sound like a track that just can’t make up its mind.

Da-da-da-da-da-da-da-dah-da-da BOOM

There is another way you can talk politics without words and for an example of how it’s done, we’re going all the way back to 1812.

Well, strictly speaking it’s to 1880, the year that Tchaikovsky wrote his 1812 Overture, a celebration of Tsarist Russia defeating Napoleon’s invading army. Over its 15 minutes, the composer uses two key techniques to tell the story of how the Russians repelled the French. In modern parlance, we’d call them samples.

First, Tchaikovsky references pieces of music that his audience would recognise and from which they could derive specific meanings. When the booming notes of La Marseillaise – the French national anthem – begin to overwhelm the piece’s opening allusions to Eastern Orthodox hymns and Russian folk melodies, it represents Napoleon’s initial success. But eventually, the Russians fight back and the overture concludes with the triumphant melody of Russia’s national anthem, God Save the Tsar.

As well as music, Tchaikovsky also employs the unmistakable sound of cannon fire. Given that this was well before the days of E-Mu SPs and Akai MPCs, performances of the 1812 Overture used live artillery for the climactic explosions that have helped it become one of the most well-known and beloved pieces of music in the world (and an essential part of any fireworks display).

Though the 1812 Overture is essentially a commissioned piece of high-class propaganda, Tchaikovsky provided a template that musicians with more of an anti-establishment viewpoint could use to create wordless political and social messages that still resonate with audiences. More than a century later, a pair of London-based producers used the form to fabulous effect.

As mid-80s DJs with a love of hip-hop, Matt Black and Jonathan More frequently referenced other music in their creations, which they released under the moniker Coldcut. The pair’s first single Say Kids What Time Is It? is potentially one of the first tracks made up entirely of samples.

Their big break came when they remixed Eric B and Rakim’s Paid in Full, transforming it into a seven-minute cavalcade of cuts from other records that incorporated Israeli folk, James Brown, sound effects albums and movie dialogue.

At the same time as producing hit singles for the likes of Yazz and Lisa Stanfield, Coldcut also began experimenting with cutting edge audio-visual technology to make promo videos, while introducing sophisticated multimedia elements to their live DJ sets.

While most DJs and producers were familiar with sampling music, Coldcut became a pioneer of sampling sounds. Just as Tchaikovsky used the brutal boom of cannon fire, so Black and More used the violent noise of another machine of destruction to send a message to the world.

Timber opens with a pulsing, wheezy rhythm that sounds like someone using a saw. This sense is confirmed by a shocking splintering noise followed by the rumbling rip of roots and the crashing crescendo of a tree falling to the ground. Then a series of eerily familiar beeps: dot dot dot dash dash dash dot dot dot. S.O.S.

Now the clang of an axe rings out repeatedly, creating a choppy rhythm. Next comes the raspy stutter of an engine starting until it finally kicks in and we first hear Timber’s extraordinary chainsaw hook.

Each of these sounds were cut from a Greenpeace video about the destruction of the Amazon rainforests by logging corporations and the impact of their rapacious harvest on the local environment, indigenous populations and the earth’s climate.

In a mere 80 seconds, Coldcut highlight the horror and hopelessness of this devastation. The machines are unceasing, their relentless rhythms stripping once-lush places of their life and colour, leaving behind muddy-brown landscapes of bare earth and sad stumps.

But wait…maybe there is hope. A warm synth string floats in and the buzzing ceases. We hear a repeated chant, the chatter of a monkey then a beautiful, aching woman’s voice singing in an unknowable language.

Though you don’t comprehend her words or recognize the tune, you understand its tribal origin. This sample tells us what we need to know about the people and the place that this singer and her song represents. We realise what’s at stake here. These people, animals and their ecosystem are under threat and must be saved.

Yet there’s something uncanny about their presence. The samples are distorted, slightly fuzzy and cut up, denuded of their naturalism by the machines that captured and manipulated them. It’s like a fading memory, a glitchy record of what we're about to lose and can never truly replace. And all the while, in the background is that faint clang of an axe, still wreaking its havoc and coming ever closer.

The engines restart, the chainsaw rhythm takes over again, while that wordless chant repeats its desperate appeal. Eventually the machines overwhelm the track, they’re everywhere, attacking from all sides. As Timber closes, they finally fade out leaving that mechanical melody, but it doesn’t represent a victory. The axmen have moved on leaving behind a ghostly voice singing a final farewell.

When I first heard Timber as a teenager, it was in conjunction with its astonishing video where every sound is matched by its visual source in a ferocious cut’n’paste collaboration. It opened my mind to the political possibilities of art that didn’t explain itself in words, to the potency of juxtaposition and contrast and for the potential of rhythms to represent both joy and terror.

Like the 1812 Overture, Timber is not subtle. But it is powerful. Its wordless collage of found sounds and meaningful melodies forms a political and social statement about the careless abuse of our natural resources and each other. The tragedy is that this truly musical message remains as depressingly relevant today as it did a quarter of a century ago.

If you like this song, try:

Atomic Moog 2000

Doctorin' the House (feat. Yazz and the Plastic Population)

True Skool (feat. Roots Manuva)

Paid in Full (Coldcut's Seven Minutes of Madness remix) - Eric B & Rakim

Go to 68: Take Me Out by Franz Ferdinand

Go to 70: Rock Steady by Aretha Franklin

Comments

Post a Comment